English version

¿Qué estaba haciendo a las 18:58 de la tarde del sábado 16 de abril? Las respuestas seguramente serán de lo más diversas. Pero, ¿cuándo dejó de temblar la tierra? Con certeza, todos hicimos lo mismo: asegurarnos de que estábamos bien, cerciorarnos de que nuestros seres queridos también lo estaban y tratar de informarnos de lo que había sucedido.

En el Ecuador pasaron más de dos horas, antes de que los medios nacionales emitieran la noticia de que se había producido un terremoto. La información ya había sido difundida por la mayor parte de las cadenas de noticias internacionales. ¿Qué pasó en esas dos horas?

Esos minutos, esas horas de desinformación, eran una eternidad en las zonas donde el terremoto de 7.8 grados había golpeado con mayor fuerza: Muisne, Pedernales, Canoa, Bahía, San Vicente, Chone, Manta y Portoviejo. No había electricidad y, con ella, desapareció el Internet. La telefonía móvil se mantuvo hasta que se acabaron las baterías de los celulares. En el espacio radioeléctrico solo había ruido blanco. Los canales de TV local tampoco emitían ninguna señal. El vacío, como si se tratara de una de aquellas películas catastróficas de los años 50.

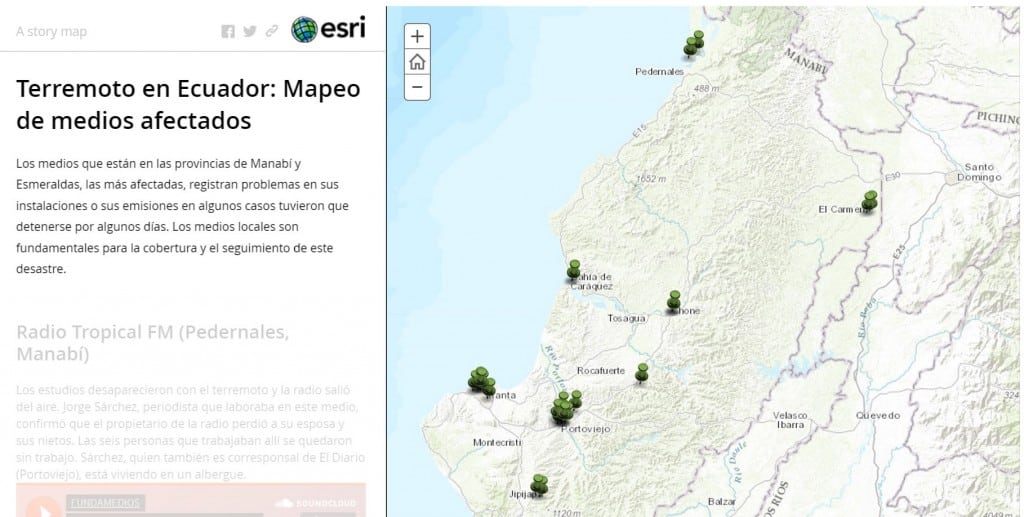

Solo que esto no era una película y detrás del silencio había tragedia. Casi la totalidad de los 86 medios locales en Manabí y Esmeraldas dejaron de transmitir. Pero 16 de ellos tuvieron daños severos: el derrumbe total de sus instalaciones, la muerte de trabajadores y familiares, afectaciones estructurales irreparables, averías en los equipos de transmisión…

Otros 19 medios presentaron perjuicios que significaron su silencio hasta por 48 horas después del momento de la catástrofe.

Oscuridad, gritos de las víctimas y el mundo desplomándose alrededor. La desolación y la desesperación. Pasado ese terror paralizante había que afrontar el desastre cuya dimensión hasta el momento era desconocida. En los minutos posteriores al terremoto, tres estaciones radiales y un canal de televisión se enlazaron para brindar a Manabí la poca información oficial que tenían hasta el momento. Acoplados con un generador eléctrico a diésel, una emisora hizo de matriz. Otra, solo puso la señal de transmisión, pues sus estudios se habían derrumbado. Se enlazaron aunque bajo la esquizofrénica legislación de medios del Ecuador, se arriesgaban a una sanción. Pues de un lado la Ley de Comunicación permite el enlace de medios, pero la Ley de Telecomunicaciones establece que estos enlaces se pueden hacer solo con previa notificación a la Agencia de Regulación y Control de las Telecomunicaciones (Arcotel). “Alguien debía decir algo, nosotros avisamos que no había alerta de tsunami. Cumplimos con nuestro deber de informar”, narra el trabajador de un medio.

Si algo se ha encontrado durante la tarea de recopilar información acerca de los medios y periodistas afectados por el terremoto, es una voluntad indomable por volver a comunicar lo más pronto posible, aunque las condiciones de trabajo de los medios de comunicación se complicaron a partir del terremoto, no solo por los daños en sus instalaciones o equipos, sino también porque muchos trabajadores sufrieron pérdidas familiares y materiales. Fundamedios identificó a más de 80 empleados, entre periodistas, operadores de radio, técnicos y otros trabajadores, que sufrieron afectaciones directas en sus viviendas y con sus familias.

El caso más grave es el de Pedernales, epicentro del terremoto. Las dos únicas radios con sede en esa ciudad, Altamar y Tropical FM, quedaron reducidas a escombros. Algunos de sus trabajadores también lo perdieron todo y ahora viven en albergues.

“Radio Tropical desapareció, yo vi como se desplomó el edificio de la radio”, cuenta Jorge Sárchez, quien trabajaba en esa estación. En esa edificación fallecieron la esposa, la hija y los tres nietos de Marcelo Cepeda, dueño del medio de comunicación.

Jorge actualmente permanece en un albergue en El Carmen y sobrevive con la ayuda de familiares y amigos. Dice que él es el más perjudicado de los seis colaboradores de la radio porque su vivienda se destruyó cuando la casa de su vecino se vino encima de la suya. También es corresponsal de El Diario, pero no tiene computadora para trabajar.

Altamar, en cambio, ya está al aire desde un estudio improvisado al lado de los escombros de lo que fueron los estudios de la radio. Funcionan con equipos prestados que trajeron desde Portoviejo. “Estamos bajo los escombros pero usamos un slogan: ‘No nos vamos, nos quedamos en Pedernales’. Ha pegado muchísimo porque una vez que salió la radio al aire la gente se empezó a motivar”, asegura el periodista Aquiles Zambrano.

Los medios con daños severos se ubican además en Portoviejo, Manta, Bahía de Caráquez y Chone. De los 14 mapeados por Fundamedios, seis continúan fuera del aire debido a graves daños en sus equipos e infraestructura.

Entre ellos está, por ejemplo, Bahía Stereo FM que funcionaba en un centro comercial que se desplomó. Su propietario, Trajano Velasteguí, estima unos USD 10.000 en pérdidas, entre las consolas que se dañaron y las antenas que perdieron. “Estamos tratando de conseguir equipo de emergencia, estoy contactándome con amigos fuera de la ciudad para que nos ayuden”, contó.

Radio Farra, La Voz del Espíritu Santo de Dios y FB Radio siguen fuera del aire (hasta el corte de este informe) pero buscan equipos prestados y nuevos lugares para reestablecer su señal.

Pero del desastre también salen otras historias positivas. Algunos medios han improvisado estudios para operar o han tenido que alquilar lugares. TV Manabita, por ejemplo, está saliendo al aire desde la Universidad San Gregorio ante los graves daños que sufrieron sus estudios. El diario El Mercurio circula con solo ocho páginas (normalmente tiene 32) y se está imprimiendo particularmente después de que su rotativa fuera gravemente afectada.

En la hora de los grandes medios globales, de las redes sociales que parecen unificar a seres de todo el mundo y de gigantescas filtraciones periodísticas de dimensión planetaria; el valor de los pequeños medios locales es inmenso. De hecho, es imposible pensar en que una comunidad se desarrolle si no cuenta con medios donde los ciudadanos puedan informarse de su realidad más cercana, opinar, debatir o vigilar y pedir cuentas a las autoridades públicas.

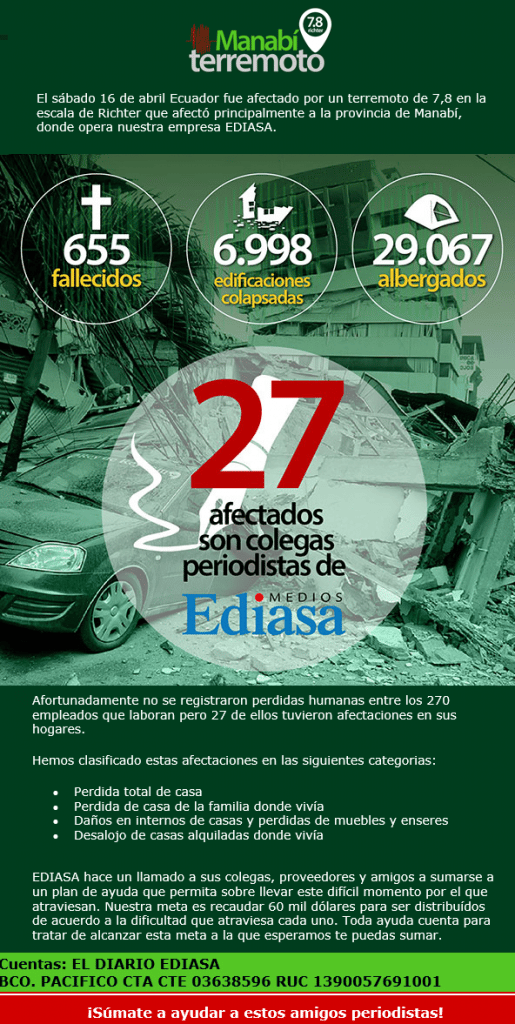

En las zonas afectadas por el terremoto, gran parte de los medios han sufrido grandes daños y decenas de trabajadores de la prensa han perdido empleos, familias, bienes. Es necesario pensar en ellos cuando se hable de solidaridad. Fundamedios junto con otras entidades periodísticas y mediáticas del país iniciará el 03 de de mayo, Día Mundial de la Libertad de Prensa, una campaña para ayudar a estas pequeñas y medianas empresas de medios y a sus trabajadores. Hoy mismo nos sumamos al llamado que se hace para ayudar a los 27 trabajadores afectados en Ediasa, la empresa editora de El Diario.

Es hora de pensar en ellos, cuando desde el Estado se anuncia la reconstrucción de las zonas devastadas . Por ejemplo, ¿se puede seguir sosteniendo un concurso para la adjudicación de 120 frecuencias en esa zona con medios semidestruidos? ¿Las autoridades de comunicación y telecomunicación pueden ser tan indolentes a lo que está sucediendo?

Media outlets and journalists: The other victims of the Ecuador earthquake

What were you doing at 18:58 on Saturday 16 April? The answers to this question will be quite diverse. But how would you answer ‘what were you doing when the earth stopped shaking’? Certainly, we all reacted in the same way: ensuring that everyone was alright, checking in on our loved ones who were likely doing the same and trying to reach us to let us know what happened.

In Ecuador, more than two hours passed before the national media circulated the news that there had been an earthquake. This information had already been distributed by most of the international news agencies. What was going on during those two hours?

Those minutes, those hours of misinformation, felt like an eternity in the areas where the 7.8 earthquake struck with the most intensity: Muisne, Pedernales, Canoa, Bahía, San Vicente, Chone, Manta and Portoviejo. There was no electricity and therefore no access to the Internet. Mobile phone communication could continue until the phones’ batteries ran out. On the radio there was silence. The local TV channels also stopped broadcasting. There was a quiet, reminiscent of a 1950s style disaster movie.

Except this wasn’t a film and behind the silence tragedy was unfolding. Almost all of the 86 local media outlets in Manabí and Esmeraldas stopped broadcasting. But 16 of those suffered severe damage: their facilities were demolished, some of their employees or their relatives were killed, they suffered irreparable structural damage, or their transmission equipment broke down.

Another 19 media outlets were affected and forced off the air for up to 48 hours from the moment disaster struck.

The initial scenes were marked by darkness, shouts from the victims, the world around them collapsing, desolation and despair. Once this paralysing fear passed one had to face the reality of the situation whose full impact was unknown at that moment. Soon after the earthquake struck, three radio stations and one TV channel began to work together to bring to Manabí residents the little official information that was available at that moment. Depending on a diesel electric generator, one of the stations served as the headquarters; another station could only emit the broadcasting signal, as their studios had been destroyed. The stations did this in coordination with each other, even though they risked a penalty for their actions under the schizophrenic legislation that governs media in Ecuador. On the one hand the Communication Law allows connections between media outlets – however, the Telecommunications Law stipulates that such links can only be established after prior notification to the Agency of Regulation and Control of Telecommunications (Agencia de Regulación y Control de las Telecomunicaciones, Arcotel). “Someone needed to say something, we informed everyone that there was no tsunami warning. We were doing our job, trying to inform people,” explained one of the media outlets.

If there was anything that stands out from Fundamedios’ research on how the media and journalists were impacted in the earthquake, it is the unbeatable will of the media outlets to get back to the task of communicating as soon as possible, undaunted by the challenges that were facing them. These challenges stemmed from the damage incurred by their offices and equipment, but also from the fact that some of their staff lost family members or their property. Fundamedios found that more than 80 members of the media, among them journalists, radio station operators, technicians and others, were directly impacted by the earthquake, either by losing a loved one or having their home destroyed.

The most serious case was in Pedernales, the epicentre of the earthquake. The only two radio stations based in this city, Altamar and Tropical FM, were reduced to rubble. Some of their workers lost everything and now live in shelters.

“Radio Tropical disappeared. I watched the station’s building collapse,” said Jorge Sárchez who worked at the station. The station’s owner, Marcelo Cepeda, lost his wife, daughter and three grandchildren, all of whom were inside the building.

Jorge is now staying in a shelter in El Carmen and is getting by with help from family and friends. He said that of the six employees at the station, he has been impacted the most as his home was completely destroyed when his neighbour’s house collapsed on top of his. He is also a correspondent for El Diario newspaper, but he doesn’t have a computer that he can do his work on.

Altamar, in contrast, is already back on air operating from a makeshift studio set up next to the remains of the station’s former studios. They are using borrowed equipment that was brought from Portoviejo. “We are under the rubble but we are using this slogan: ‘We are not going anywhere, we are staying in Pedernales.’ It really struck a chord because as soon as the radio station was back on the air people were inspired,“ said journalist Aquiles Zambrano.

Other media outlets that suffered serious damage are located in Portoviejo, Manta, Bahía de Caráquez and Chone. Of the 14 that were identified by Fundamedios, six are still off the air due to serious damage to their equipment and infrastructure. Among these is, for example, Bahía Stereo FM that used to operate in a commercial centre that collapsed. Station owner Trajano Velasteguí estimates the losses at around US$10,000, due to the damage to the control panels and the antennas. “We are trying to find some equipment to use temporarily, I am in contact with friends outside the city to ask for their help,” he explained.

Radio Farra, Sono Onda, La Voz del Espíritu Santo de Dios and FB Radio are still off the air but are also looking for equipment they could borrow and new locations from where they can relaunch their transmissions.

At the same time, there were some positive stories coming out of this disaster. Some of the media outlets were able to set up impromptu studios so they could operate or had to rent space. TV Manabita, for example, is broadcasting from the University San Gregorio as their studios were seriously affected. The El Mercurio newspaper remains in circulation with an edition of eight pages (normally it has 32) and is continuing to print even though its printing press was damaged.

In an era of mass global media, social networks that seem to unify people from all over and a massive flow of information that travels the world, the importance of small local media is still immense. It is impossible to imagine how a community can develop without access to local news sources so that people can be informed about their own communities, and a forum where they can share their opinion, oversee and debate the actions of government officials and demand accountability.

In the regions that were impacted by the earthquake, a large number of media outlets have suffered damage and dozens of press workers have lost their jobs, their loved ones or their belongings. On 3 May, World Press Freedom Day, Fundamedios, together with other press and media organisations, will launch a campaign to help these small and medium sized media outlets and their staff. And we also add our voice to the call for assistance for the 27 Ediasa workers who were impacted. El Diario newspaper is published by Ediasa.

The impact on these media outlets and journalists must be taken into consideration, as the State announces its plans for the reconstruction of the decimated zones. For example, will it be possible to continue the conversation about the allocation of 120 broadcasting frequencies in the region when so many media are in this state of disrepair? Could the communications and telecommunications authorities be that indifferent to what is happening?

Documentos asociados